By Cheikhna Bounajim Cissé, author of “FCFA – Face Cachée de la Finance Africaine” (BoD, 2019), analyzes the challenges and contours of the future single currency of ECOWAS.

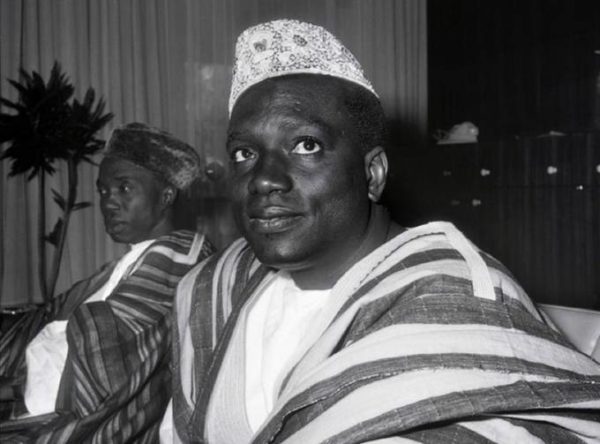

Former Malian President Modibo Keïta was a visionary. Two years after the independence of his country proclaimed on September 22, 1960, he made the choice of monetary sovereignty. Mali abandoned the CFA franc to mint its own currency, the Malian franc. This monetary experience could have been beneficial to the country and to the entire continent. Unfortunately, trapped by internal divisions and France’s fierce determination not to let the Guinean precedent recur, it faded on July 1, 1984 by the reintegration of Mali into the CFA zone.

Everywhere and at all times, money is an essential attribute of sovereignty, a sovereign prerogative. It is also a hunting tool, an instrument of domination, in the hands of those who guarantee it, manufacture it, issue it, create it and circulate it.

On June 30, 1962, Malian President Modibo Keïta declared to his country’s National Assembly: “You don’t need to be an economist to know that money, at the national level, is both a guarantee of freedom and, better yet, an instrument of power. Guarantee of freedom, because it allows us, not to do what we want, but rather to act in the sense of the national interest. Instrument of power – insofar as it gives us the ability to coerce economic feudalism and pressure groups that want to ignore the national interest and only defend the exorbitant privileges inherited from the dying colonial regime. ”

On July 1, 1962, the Malian president went from speech to action. He abandoned the CFA franc and created the Malian franc, whose banknotes and coins were made in Czechoslovakia. The academic Guia Migani looks back on this hilly episode in Franco-Malian relations: “[…] On June 30, 1962, Bamako warned Paris that from the next day the CFA franc would cease to have legal power over its territory. It will be replaced by a Malian franc which will have a value equal to that of the CFA franc. In a speech to Parliament, [Malian President] Modibo Keita presents the reform as the normal culmination of Mali’s political and economic independence: “The national currency […] is a guarantee of freedom and an instrument of power. Its success is nevertheless subordinate to the confidence that the Malians will place in it and above all on the discipline which must be followed and which will imply in particular a strengthening of the austerity of the budget and finances [1]. ”

However, continues the French academic, the Malian government was worried. He knew that he did not fully control the population and that the collaboration of Paris was necessary for him not to be obliged to immediately face the economic consequences of his act. This is why, from the start, Modibo Keita hastened to declare that the reform, leading to Mali’s departure from the West African Monetary Union, was taken in accordance with the Franco-Malian agreements of March 9, 1962. These recognized Mali’s right to create a national currency and an issuing institution. In addition, Mali considered that it was entitled to the opening of an advance account promised, in its opinion, by the agreements.

In Modibo Keita’s message to General de Gaulle, he wrote that monetary reform “should not be interpreted as a gesture of defiance, let alone hostility towards anyone. Of course, the immediate consequence of the choice we made is the exit of Mali from the West African Monetary Union […]. But, while recognizing the need for an essential reorganization of our relations with the whole of the franc zone to adapt them to the new situation thus created, it remains obvious that our departure from the Monetary Union cannot call into question the the very principle of our belonging to the said franc zone. ”

The creation of the Malian franc was painful. According to the French ambassador to Mali at the time, the reform was received by the population calmly. On the other hand, it worried the business community a lot. Foreign companies considered abandoning the country.

On July 20, 1962, economic operators took to the streets in Bamako to express their concerns about the consequences of the monetary reform on their businesses. According to some sources, the demonstrators gathered around the French embassy chanted slogans hostile to the regime in place and favorable to France: “Down with the Malian franc, down with Modibo, long live General de Gaulle”. The central government saw the hand of the political opposition behind the demonstrators. Their reaction was not long in coming. Several traders and politicians were arrested on July 23, 1962, including the two opposition leaders Fily Dabo Sissoko and Hammadoun Dicko, both former members of the French National Assembly and former members of the French government. They joined El Hadj Kassoum Touré, known as Maraba Kassoum, imprisoned three days earlier. All were indicted and sent to a popular court for endangering state security. The trial, chaired by political commissar Mamadou Diarrah and comprising 39 jurors, took place from July 24 to 27, 1962. The verdict fell on October 1, 1962. The three main defendants received the death penalty, later commuted – under pressure of the international community – under sentence of hard labor for life. Two years later, they died in Kidal prison, in murky circumstances that had not yet been clarified.

After five years of difficult gestation, the situation in Mali presented itself through the “siege”, as obstetricians would put it when describing the position of an ill-engaged baby. The breathless Malian franc could no longer be carried by a breathless national economy. Faced with enormous internal difficulties, the Malian authorities appealed to France to reintegrate their country into the CFA zone. This “comeback” which required two major devaluations of the Malian franc (1963 and 1967) was relentless. Finally, in June 1984, after endless and intense negotiations with France, Mali abdicated its monetary sovereignty in order to assume French monetary supervision. He was again authorized to use the CFA franc as the official currency. By remaining firm and resolutely determined to thwart Mali’s monetary irredentism, France wanted to make this case an example for all its former colonies who would venture to create their own currency. Indeed, the failure of this Malian experiment, poorly prepared internally and harshly fought by the old metropolis, was more than dissuasive for the other members of the franc zone who gave up the “freedom to go bankrupt” .

Four decades ago, the spirited professor Joseph Tchundjang Pouemi allowed himself a premonitory warning: “An independent currency is not only possible, it is essential to an economic policy that would be national. “Subsequently, the Cameroonian economist, with proven firmness and rigorous reasoning, hastened to add a codicil:” It is still necessary to make good use of it, to manage it well and first of all to understand it well. where it comes from and what it is for, otherwise it is likely to be self-suppressed. “