Amputated from its North as is the case in all the reports of the Bretton Wood institutions, sub-Saharan Africa will be the region of the world which will post the lowest growth in 2021. This is what the latest IMF report indicates. , published in April 2021 with, it must be said, a pessimism still in place but, we are pleased, attenuated compared to the alarmism of October 2020 of the said organization.

According to the IMF, between the southern edge of the Sahara and Cape Town, the GDP contraction was 1.9% in 2020, significantly better than the -3% predicted in October. But it is the worst result ever for the region.

Employment fell by about 81⁄2% in 2020, more than 32 million people slipped into extreme poverty, and disruptions in education hurt the prospects of a generation of students.

In 2021, however, the region will grow by 3.4% (compared to a forecast of 3.1% in October) driven by increased exports and commodity prices. At the same time, global growth will be 6% driven by the progress of vaccination campaigns.

In this regard, sub-Saharan Africa is lagging behind and should not reach the theoretical point of collective immunization (vaccination of at least 60% of the population) before 2023.

Slowness detrimental to the economy but explained by the access to vaccines. “For most countries, the cost of immunizing 60% of the population will be high: it will represent an increase in existing health spending of up to 50%,” says the IMF.

In this context, says the keystone of international monetary institutions, “it is only after 2022 that per capita production should return to 2019 levels. In many countries, per capita income will not return to low levels. pre-crisis levels before 2025 ”.

Despite a smaller health impact than in the rest of the world, the land that the philosopher Hegel placed out of history has the highest economic impact in relation to Covid-19. “The cumulative production losses attributable to the pandemic will represent nearly 12% of GDP in 2020–21”, estimates the IMF which fears a health situation with episodes of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) repeating before vaccines do not become accessible to all.

Other factors of uncertainty pointed out by the report include access to external financing (official and private), political instability and new climatic shocks, for example floods or droughts.

Despite this difficult situation for sub-Saharan Africa, the IMF recommends that, in the long term, public finances will have to be restored. Against the backdrop of tight fiscal space, deficits in the region are expected to decline to just over 11⁄2 percent of GDP in 2021, bringing the average debt down to around 56 percent of GDP.

In all, 17 countries were in debt distress or were at high risk of debt distress in 2020, one more than before the crisis. This number encompasses several small or fragile countries and represents about a quarter of the region’s GDP, or 17% of its outstanding debt. These ratios, relatively moderate compared to the rest of the world, agree with Beninese economist Lionel Zinsou, who nicely declared last week that a few trees should not hide the rainforest.

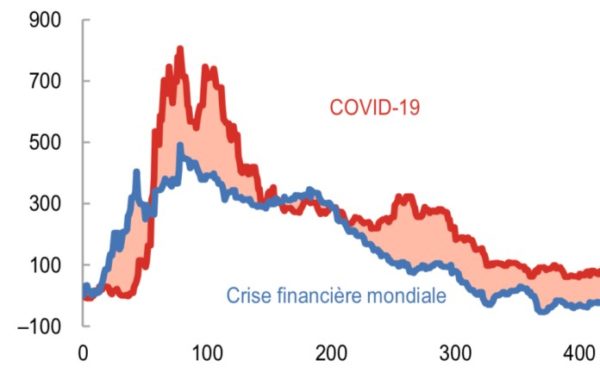

In its recommendations, the IMF pleads for the broadening of the tax base (a sensitive chord because of the social cost) wrapped in the neutral formula of “domestic resource mobilization”. The leaders, attentive to a tense political context in general, will always have recourse to external debt. The observed yield spreads on sovereign bonds in sub-Saharan Africa, which reached record levels in April, have narrowed by around 700 basis points in the course of 2020, which in itself is a sign that harsh forecasts issued for Africa last spring were undermined by, it cannot be said enough, a reality much less harsh than the perception and associated rates of return for risk.

On this debt issue, the Group of Twenty (G20) debt service suspension initiative provided valuable liquidity support, namely $ 1.8 billion in aid between June and December 2020 and a potential saving of 4.8 billion dollars between January and June 2021. To this process, it will be necessary to add (the IMF report does not mention it because it was certainly completed before) the recent initiative of the issue of SDRs ( Special Drawing Rights) from the IMF with an impact range between 33 and 100 billion dollars, or 1.5 to 4% of GDP growth. Does this mean that the outlook for the IMF report should be revised upwards?