By Adama Gaye

It is never by chance that the Chinese President, now considered the most powerful man in the world *, leaves his country. That gives all the meaning of the stay, the antipodes, that Xi Jinping, carries out, from this weekend, on the African continent. Does it come to walk in the footsteps, or flowerbeds, of its predecessors who have already done the safari, reaffirming the dogmas and paradigms that have irrigated the Sino-African relationship since, in particular, the introduction, in 1949, of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) following the triumph of the Maoist Communists against Chiang-kai Tchek Nationalists? Or will it be an opportunity for a reset, a reset, according to a strategy popularized by former US President Barack Obama? He arrives on the continent in a context where there is urgency to offer the Sino-African relationship new perspectives. In a word, to open new paths, far from those, beaten, obsolete and subject to the question, in many African circles.

Four countries – Senegal, Rwanda, South Africa, Mauritius – are on the agenda of this African tour of the strongest man in the world’s most populous country, the world’s largest economy in purchasing power parity (PPP), and global issue of geo-economic and even geopolitical rivalries.

The need for an aggiornamento has never been so obvious to restore breath to a relationship, more questionable than one imagines, even if it is qualified as strategic by the actors it federates. Obviously, it should no longer postpone this review without which its future could be compromised …

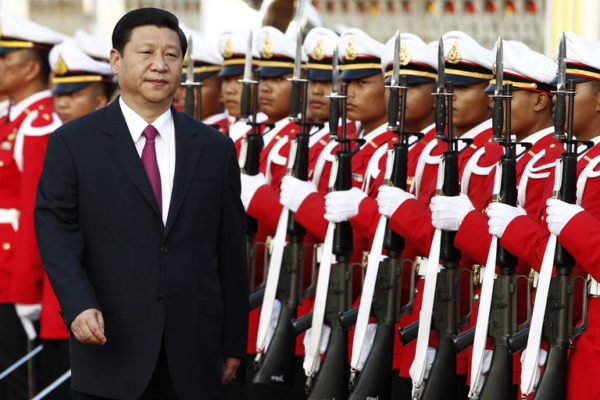

What makes it imperative, by making it easier, this collapse, is essentially the fact that the man who now heads China, newly reelected at the head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the eponymous state, has a magisterial mandate conferring on him, more than a legitimacy, a stranglehold on all the levers of command of his country. Never since the death of Mao Tse-tung, father of Communist China, of which he led the liberation struggle, to draw her from a century of quasi-colonial rule (1840-1949), had no man such an ascendancy over the one billion and three hundred million people of China. Even Deng Xiao-ping, one of his most famous successors, could not have so much control over the country. This, despite its father’s will of economic reforms and the opening of the country, in 1978, bases of the conversion to the market economy and the economic rise that have transformed China. The other Chinese leaders, Zhu Rong-ji, Jiang Zemin, Wen Jia-bao or Hu Jintao, already stripped of the tablets of history, are far behind him. Xi is from another class! How many ancestral emperors have had as much power as him? Very little, or almost no …

New emperor

The Xi era is not just that of a princeling, a red prince descended from one of the father-founders of present-day China. We are dealing with a neo-emperor with exorbitant powers – and feared by all! His name appears on the CCP Constitution, a privilege he shares only with Mao and Deng, with the advantage of having carte blanche to control the country’s real counterpowers. Nothing prevents the extension of his leadership ad-vitaem, the limitation on two terms of five years having been conveniently removed to put him at ease; while the national and local state and political authorities are under his control, riddled with his supporters.

Its power terrifies the CCP’s hierarchical, local businessmen and ordinary people. Many of them languish in jail, imprisoned like the all-powerful trade minister, Bo Xilai, for being accused of corruption, others likely to have crossed over a red line, suspected of omnipotence of the new emperor.

Already, in December 2015, when he had not yet raised his status to a stratospheric level, he had shown his striking force to his African colleagues, suddenly dwarfs before his eyes, while they met together in Johannesburg in the triennial dialogue established under the auspices of the China-Africa Cooperation Forum (Focac). A month earlier, in Malta, the European Union caught in its fears of migrants and ankylosed by its anemic economic growth had been able to offer a meager 2 billion euros to Africa in a summit focused on the problem the containment of international migration.

Under wraps, the Europeans laughed no less, laughing at the ebb of Chinese growth and the collapse of its foreign currency reserves. All expected a withdrawal of Beijing from its massive African trade and diplomatic commitments. Now, surprising his African interlocutors, and as a snub to the classical actors, European and American, believing in hunting on the continent, so that in front of a desk to which all eyes were turned, the center of the conventions of the South African economic capital, it is an imperial Xi Jinping who announces that his country would devote 60 billion dollars to Africa over the next three years. Who did not notice, that day, the broad smile and the ample gestures of the then president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe? It’s like he wants to say, “Here’s the real friend of Africa!”

Since then, Xi Jinping, become the equivalent, on paper, of the Grand Timonier, that was the reference contiguous to Mao, is not therefore a banal visitor who, in July, arrives in Africa. Here, as elsewhere, the context is changing. It is marked by major mutations, reversals of alliances, commercial and economic rivalries, against the backdrop of the revival of military-industrial competitions and the fight against new asymmetric and even emerging dangers and pandemics.

One could, at first glance, wonder why his visit would change relations tested since they found their base at the conference of Bandoeng in April 1955 which made meet, at this moment of birth of the third-world, leaders Chinese and African nationalists in search of their independence for most of them … A man represented China, Zhou Enlai. Mao’s right arm, he was the one he sent to make the first tour of a great Chinese leader on the continent. We are in 1963. The opportunity for him to decline what was the basis of Chinese cooperation in Africa, including an ideological fraternity, the refusal of any interference in internal affairs, peaceful coexistence or the non-negotiability of a single China, including the island of Taiwan that Beijing considers rebel.

In the fervor of the ideological conflicts of the cold war, by cultivating its originality, to no longer be a dependency of Moscow, Maoist China was however not able to do more than a cooperation of the poor with the continent. His barefoot doctors, his agricultural assistants deployed in the depths of Africa, were his signature on the spot. Only the rattling of arms delivered to his partners in liberation struggles could mean that his ambitions were not limited to symbolic gestures. Its financing of the Tanzania-Zambia (Tazara) railway was another. It had been decided to make up for the rejection of this project by Western countries and that of the World Bank. China had not hesitated to pour hundreds of millions of dollars, while it was going through one of its greatest torments, a murderous cultural revolution between 1966 and 1976.

She then lives tense moments, close to bankruptcy. So, when Mao died in September 1976, she had no choice but to inaugurate her own economic reforms in 1978. Because she was exiled from her cultural revolution, she had not finished the impact of the bankruptcy of the great leap forward in agriculture, Mao’s catch-up strategy of 1959, which resulted in more than thirty million deaths.

All is not rosy

The entry into the reforms makes it disappear from African radars. His return did not begin there until 1982, with a visit of his then prime minister, Zhao Ziyang, came to propose a new type of economic cooperation, on the model, in force since then, of the win-win . Very soon, the end of the cold war, the subsequent disengagement of the Western countries of the continent, and, in parallel, the diplomatic isolation of China, following the events of Tiananmen, in 1989, combine to precipitate the Sino-African rapprochement. . All the more easily as its economy, close to overheating, urgently needed natural resources to lubricate it and markets, especially in Africa, to support a commercial offensive of a magnitude never seen, China could only find this continent that its own explorers, including the famous shipowner Enuque, Zeng He, plowed peacefully, before Europe came, two centuries later, colonize it.

Since then, Sino-African relations are on a deafening slope. From less than $ 10 million in 1982, their trade, the first with Africa, is close to $ 300 billion. China is everywhere. In the retail trade. African music. The donuts. The vuvuzelas. And of course the big building sites, the roads, the railways, the mines, and also the administrative buildings, like these brand new parliaments or presidential palaces, or even these so-called stages of Friendship and the big theaters or museums. Not to mention the implementation of a great political and diplomatic ambition.

If this is so, it is because China needs natural resources, energy, and diplomatic support from the continent. In return, it arises nolens volens in alternative development model, the developmental state, giving it back colors. Without it, who would still be interested in an Africa decreed in the year 2000 as a “continent without hope”, according to the irrefutable judgment that had barred the front page of the magazine The Economist.

However, we must step over the celebration of figures, often mirobolant, and the beauty of a rhetoric that proscribes conditionality, except the clause of China alone, in this relationship between developing countries, as claimed by Beijing. In doing so, one must admit that everything is not rosy on the eve of his president’s visit to Africa.

Candide conversion

So far we can only be struck by, among other things, the racism that so many Chinese people show towards Africans. Do not speak to them above all: with a contemptuous pout, they turn their heads away. Who is not so disappointed by the cynicism, the stabbings, in short the non-respect of all the rules that the Chinese entrepreneurs adopt, like to say to their African partners that they are not bound by anything.

They often invoke Chinese culture to justify what is nothing but a cold exploitation of their relations. The poor qualities of so many Chinese products, massive corruption, collusion with public officials, unethical, over-billing or truncated bills to grab the markets with the help of “bourgeois-compradores”, and, some the say, espionage, right to the heart of the African Union, are signs of this unease that soft speech can no longer cover. How could one, similarly, not give right to skeptics, many, who think that China would resume a colonial model by refusing to bring value on the continent? They reproached him for being content to reproduce the old colonial model, in other words to import African raw materials for trivial things and then to sell to this continent at the bottom of the value chain its own manufactured products.

One may even wonder whether this continent, which has already been molded to multi-party democracy, has an interest in dropping its gains in this area to embrace a vertical, stato-centered “model” that Beijing refuses, for its part, to consider exportable. .

Obviously, on a tangible basis of a relationship established several centuries ago but consolidated by a community of interests, ideological or economic, the time for a candid conversation has come: not to be lulled by the illusions of an intoxicating rhetoric. These are not the relocations of industrial parks to Africa nor the huge promises of investment brought by the major project of Xi Jinping – $ 1000 billion- to revive the Silk Road and preserve his country from a maritime strangulation American, which should ignore this reset, this redefinition of the terms of the Sino-African dialogue.

Now that only Swaziland remains without diplomatic relations with it, China no longer has the excuse not to accept an open-hearted conversation with Africa. Without this, to envisage the Sino-African connection under a strategic prism raises dreams of an impossible big night …

Can we put the craft back on the work? That’s why President Xi Jinping’s African trip deserves to be described as historic. Beyond the changes in the emerging countries gathered in the group of Brics, in conclave in South Africa, a factor explaining his return to this country, it is directly with the African states that the Chinese President is invited to pose the appropriate acts to free the Sino-African relationship of gravity, more and more visible, which gangrene. The African people, more than some corrupt African leaders, are more than ever greedy. They demand it. Silently ! Will it be taken into account by the next meeting in Beijing of the Sino-African Cooperation Forum in September? An imperative. Xi is, this time, highly anticipated on the continent. Watched even!

* Ps: Last year, The Economist designated Xi Jinping the most powerful man on the planet.