Up to 37% of children in school worldwide are taught in a language they do not speak at home, the World Bank finds in a new report. Read below the summary of the report signed by Jaime Saavedra, Director General, Education, Michael Crawford, Lead Education Specialist and Sergio Venegas Marin.

Teaching students in the language they understand seems to be obvious. But for many, it isn’t. Over the past decades, we have seen tremendous progress in improving access to education, but the world continues to face a global learning crisis. Although most countries have universal or near universal enrollment in primary education, learning is too low. More than half of primary school students around the world face learning poverty because they are unable to read and understand simple text by age 10. Their ability to succeed in school and to invest in themselves and in their future as adults is compromised.

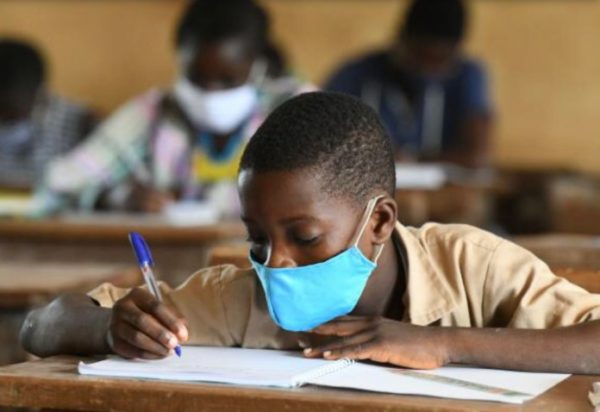

One of the reasons for this is clearly visible: up to 37% of school children around the world are taught in a language they do not speak at home and do not use and understand well. . Language of instruction policies, which should prepare children for success, too often condemn them to failure from the start of primary school.

The science of learning

The research is clear: Students learn to read and write by matching sounds and symbols in a writing system to words they learned in their parents’ language. The better their oral language skills, the faster and easier they learn to read. When confronted with an unfamiliar language in the classroom, progress becomes almost impossible. This is part of the reason why in some countries many students cannot read any words and only know a few names of letters in the language they are to learn. They are in school, their parents assume they are learning, but they are not. This happens to Nigerian children who should receive education in Hausa, Haitian children who should receive education in Haitian Creole, and Mozambican children who should receive education in makua (also written macua or makhuwa).

The new World Bank report highlights the many ways the situation can and must be improved. When students are taught in the language they speak and understand well, they learn to read better and faster. They are also in a better position to learn a second language, to master other academic content such as math, science and history, and to fully develop their cognitive skills. Children who learn in their mother tongue are also more likely to enroll and stay in school longer. Effective language of instruction policies improve learning and progress in school and also reduce national costs per student, allowing more efficient use of public funds to improve access and quality of education for all children.

Successful approaches to language of instruction

Countries face a wide variety of challenges. In a country, dozens of different languages can be spoken. In another, students may speak one language at home, another in the playground, and also be expected to learn in a third language, the national language. Based on these varied experiences, the report presents successful approaches: (i) teaching children in their mother tongue from early childhood education and at least until the end of primary school; (ii) use the mother tongue for teaching school subjects other than reading and writing; (iii) introduce any additional language as a subject with emphasis on oral language skills; (iv) continue to use the mother tongue for instruction in one form or another, even when another language becomes the official language of instruction; and (v) plan, develop, adapt and continuously improve the implementation of policies relating to the language of instruction.

By closely observing students’ school experiences, policymakers are orienting their school systems to be successful as they consider how to better rebuild after the COVID-19 pandemic. Systems must focus on essential learning and improve the efficiency of the teaching and learning process. Education in the appropriate languages and the implementation of effective language of instruction measures will help to achieve these goals.

Policy measures are necessary, but not enough

Although they are an important factor in promoting literacy, these language of instruction measures need to be well integrated into a wider set of literacy policies. Isolated initiatives are ineffective. There is a need for: i) political and technical commitment to literacy, which in part translates into a commitment to measure and monitor learning outcomes, ii) support for teachers in the form of lesson plans, iii ) support for teachers, iv) the provision of quality books and texts, and v) the commitment of parents and communities to encourage the love of books and reading at home.

At the same time, judicious use of technology can facilitate the implementation of the whole system and, in general, the design and implementation of good language policies and practices. Whether it’s innovative ways to map and measure the skill levels of students and teachers, to simplify the creation and adaptation of new learning materials in multiple languages, or to deliver and supplement education itself, technology produces better and more reliable tools. Many of them, like cell phone-based technologies, have become mainstream even in the poorest parts of the world. They can now make teaching in the right language faster, easier and potentially less expensive.

Ultimately, in order to fight against learning poverty, a coherent pedagogical approach is needed. An approach focused on what needs to be done to improve the teaching and learning process between student and teacher, and then looking for aligned and coordinated ways to support this at scale. A set of literacy policies in the right language can ensure basic literacy and allow for a better school experience and easier introduction of a second language. Investments in education systems around the world will not produce significant improvements in learning if, ultimately, students do not understand the language in which they are taught.

Source: the World Bank